The problem with “The Strokes changed everything” narrative about aughts indie

This was originally published on March 5, 2023 on my Substack newsletter. I’m republishing it here to get this post on my platform. (Never trust platforms you don’t own.) If you would like to support the work I do (I don’t get research funds now that I’m not faculty), I’m running a sale on newsletter subscriptions: a year for $24. Offer is good until 23 February 2024.

As the appearance of 2002 Mercury Prize nominee Mike Skinner on British producer Fred Again’s latest single attests, the wave of nostalgia for aughts indie music is growing continuously bigger. Besides making me feel old, this aughts nostalgia, especially the retromania for the indie music of the era now anachronistically referred to as “indie sleaze,” has been re-scripting the commonsense narrative of what was actually going on then and what it all meant. Today, the era’s post-punk revival is framed as the result of The Strokes’s reinvigoration of the rock scene. However, this “The Strokes changed everything” is not exactly how people understood things back in the early aughts, and it also misrepresents what The Strokes success changed: they didn’t so much reinvigorate a dying rock scene so much as make alternative rock palatable to white people with lots of cultural capital after 90s alt rock radio had done everything it could to push the genre out of fashion.

In the early 2000s, there was a huge post-punk revival, with a proliferation of bands that, for example, sound like Joy Division (Interpol), name themselves after a PiL song (Radio 4), sounded like what would have happened if The Cure signed to Factory Records (The Rapture), and rock bands that, like New Order and A Certain Ratio, explicitly made dance music (LCD Soundsystem, !!!). There were feminist and queer-forward lo-fi electronic dance music groups in what was called the electroclash scene that echoed early 80s new wave and synthpop, and bloghouse tracks often combined rock and dance in a way that evoked Madchester-y vibes. To top it off, Gang of Four reunited with its original lineup for an international tour and re-recording of their biggest album.

At the time, the consensus in the music press and among fans was that this return to post-punk was driven by the success of The Strokes 2001 album “This Is It.” In their 2001 review of the band’s album This Is It, Pitchfork notes that The Strokes have been “touted by the press as “the forefathers of a bold new era in rock”.” This “The Strokes Changed Everything” narrative was so prevalent that a 2001 article in The Fader snarkily observes that “following the fuzzy logic of phenom-based journalism, there are already more articles about the Strokes that cover them being hyped than there are ones that hype them.” Fast forward ten years, and that narrative only intensifies in strength. For example, in 2011 the BBC claims that “This Is It” “was the catalyst for a new rock revolution throughout the noughties…This It helped to kick open the door for other new American bands, including fellow New York-based acts Interpol, Yeah Yeah Yeahs and LCD Soundsystem, as well as out-of-towners Kings of Leon and The Killers….The band were greeted as rock ‘n’ roll saviours in the UK from pretty much day one.” On the other side of the pond, music journalist Ben Schweitz’s off-label 2019 update to Rolling Stone’s 500 best albums of all time begins his write up of “This Is It” with the claim that “The Strokes burst onto the music scene catapulting indie music into the mainstream.” Back in 2001 the music press was quite self-aware of all the hype surrounding The Strokes around the release of “This Is It,” and by the end of the 2010s that ironic, almost Gen-X-y self-awareness had concretized into something more like a legend as the once overhyped band came to be represented as saviors and revolutionaries.

The motivation for (mis)representing The Strokes as saviors becomes clear when we see exactly what (and whom) the band purportedly saved rock listeners from. In NME’s 2021 re-visit of the album, Rihan Daly kicks off their piece with the lede:

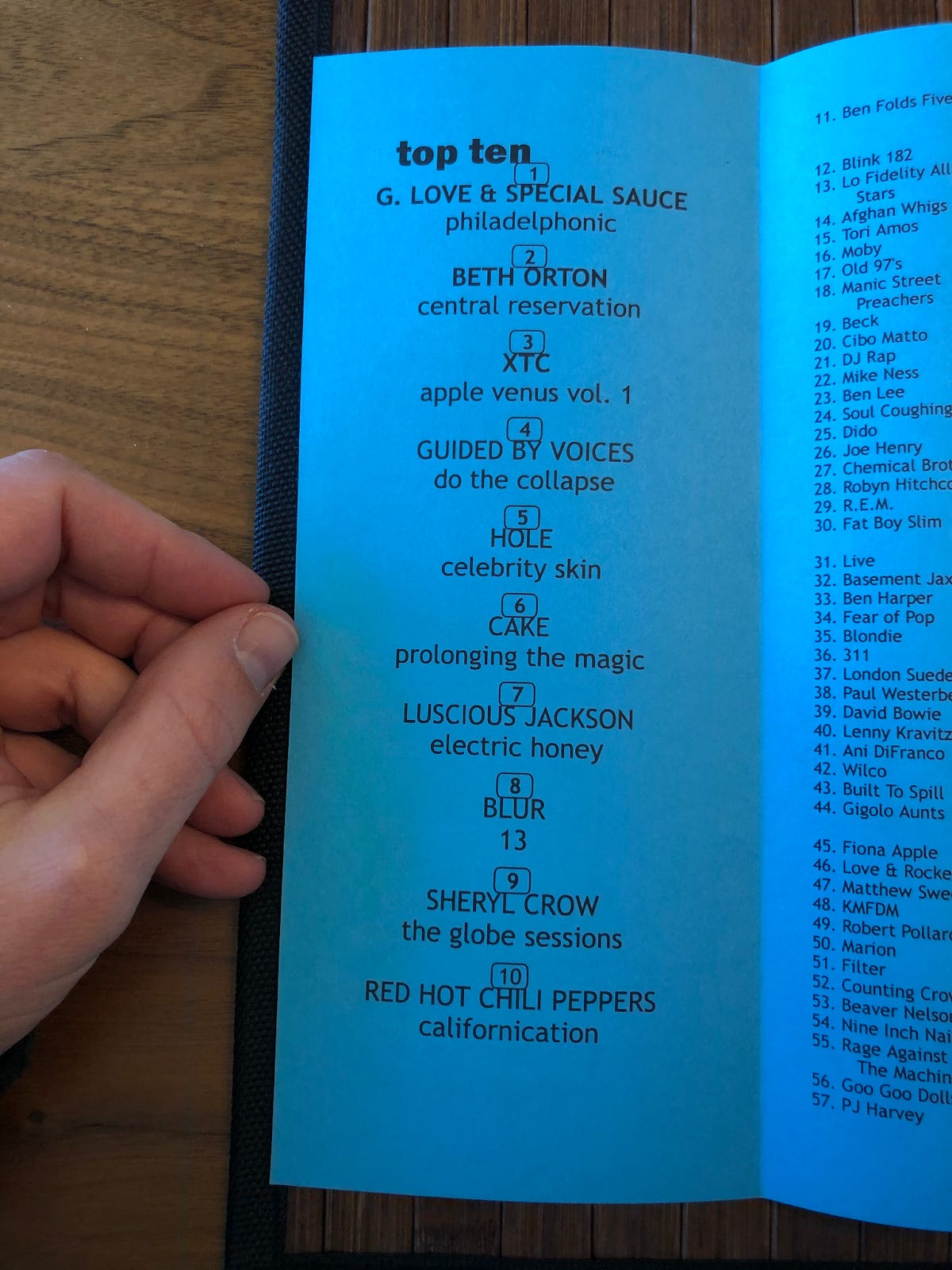

According to Daly’s account, The Strokes saved rock from nu metal, which modern rock artists like Faith No More, Rage Against The Machine, and Nine Inch Nails held in general disdain for its immaturity and red-state-y aggrieved white masculinity, and from an indie scene that was purportedly playing it too safe, stylistically. In other words, The Strokes brought the “right”—i.e., middle class, white, cishetero—masculinity back to the kind of rock that appeared on US and UK charts. In 1999, the top of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks chart was dominated by a duel between Everlast and Sugar Ray at the beginning of the year, and one between Creed, Bush, and Limp Bizkit at the end. Creed is second only to Nickelback when it comes to alt rock bands denigrated for their red-state white masculinity, and their chart dominance is the result of alt rock radio’s intentional narrowcasting to that demographic. The 1999 best of chart for venerated modern rock radio station WOXY looks very different: the top ten is full of women such as Beth Orton, Hole, Luscious Jackson, and Sheryl Crow. Representing each end of the spectrum Daly outlines, these two charts depict a rock market that culturally elite white men can’t easily see themselves in. This absence of hip white masculinity is what The Strokes purportedly saved rock from.

The Strokes were a band whose members went to boarding school in Switzerland and dated blonde actresses (drummer Fabrizio Moretti dated Drew Barrymore). Not only did the band dress like Lou Reed, with their skinny jeans and black leather jackets, they seemed like people with the cultural capital of someone married to world-renowned avant-garde musician Laurie Anderson.

The Strokes (re)gentrified rock music, making it palatable for fashionable middle- and upper-class people. I was a grad student in Chicago when “This Is It” was released, and I remember when the hippest student in the program brought the CD to the grad office and loudly sang its praises. This guy played in bands and lived above the Raw Bar next to the coolest music venue in town, The Metro/Smartbar, so if he was endorsing it that meant it was certifiably cool. And while alternative rock had spent the past five to seven years narrowcasting to white men and doubling down on a cartoony “Break Stuff” machismo, The Strokes made rock into something humanities PhD students living in a big American city would admit to listening to.

This “The Strokes changed everything” narrative does the exact same thing I show in my WOXY book that the “Nirvana changed everything” did a decade before: they re-centered hip white masculinity in the rock market. So, as aughts nostalgia continues to snowball (I just heard that new Fred Again track featuring Mike Skinner from The Streets on Radio 1 last night), it’s important that the story we tell ourselves today about that era correctly depicts what actually happened so that we don’t reinforce the sexist and racist motivations and effects of the original, mistaken narrative.

In the 2020s, we’re less likely to have an exact repeat of the “X band put white men with guitars back at the center of the rock scene” narrative because the boundaries around gender/race and genre work a bit differently now. The title of this 2021 article claims that two teen girls of color, “Olivia Rodrigo and Willow [Smith are] Bringing Rock Back to the Mainstream.” Not even twenty years after the backlash against Ashlee Simpson’s failed attempt at lip-synching on SNL spurred NY Times music critic Kelefa Sanneh to write his now-iconic essay “The Rap Against Rockism,” the music press lauds some young-girl-bosses for doing a contemporary version of what The Strokes and Nirvana did in decades past: reframing guitar-driven rock as valuable capital, cultural and otherwise. In the world of Nicki Haley and Condoleeza Rice (to say nothing of Amy Coney-Barrett), women of color are seen as legitimately occupying positions of traditional white patriarchal authority so long as they do so in ways that don’t otherwise upset the overall patriarchal racial capitalist distribution of property and personhood (think, for example, of Rice’s, Powell’s, and Obama’s role in Iraq and Afghanistan, two countries in the Global South full of brown people). And just as popular/corporate feminism and multiracial white supremacy have shifted how gender and racial identity are used to produce white supremacist capitalist patriarchy, in an increasingly post-genre world, strict genre rules and allegiances are presented as something the discerning listener has overcome. As I argued in this piece on poptimism and popular feminism, “In 2018, poptimism works more or less like popular feminism: it turns the revaluation of things traditionally devalued because of their femininity into a way to make money.” In today’s music industry, flexibility–in medium, in genre–is the way to make money: just as Billie Eilish’s “Bad Guy” finally topped the charts when a new, vertical/portrait video was cut, tracks with genre diversity, such as “Old Town Road” and its many remixes, or 24kGoldn’s “Mood” and its combination of indie rock, hip hop, and pop, tend to outperform tracks with less such diversity.

The difference between fans’ and critics’ responses to a 2001 mashup and a 2023 cover tells a similar story. Freelance Hellraiser’s 2001 mashup of The Strokes with Christina Aguleria demonstrated that “Christina Aguilera and the Strokes [were] in perfect harmony,” and this struck people even as late as 2009 as “strange.” The Strokes were proper rockers–white guys with guitars–and the thought that one of their songs was basically exactly the same as a Latina ex-Mousketeer’s pop hit suggested that rockist prejudices had no basis in the actual music itself. The idea that a “proper” rock song by white guys with guitars wasn’t inherently musically superior to a pop hit sung by a young woman of color ran counter to the very sexist and racist hierarchies rockism was designed to preserve. However, in 2023 pop hip hop star Lizzo was in fact encouraged to develop her cover of the industrial rock track “Du Hast” from a bit a few lines long into a full cover. Comments on Lizzo’s Instagram post of a video of the performance are overwhelmingly positive, and they report that Rammstein even reposted it to their stories, effectively endorsing the cover. Although there are a few rockist complaints (proportionally, about the same as the fat-shaming comments), comments tend more toward “I love that the official Rammstein account reposted this. Real recognize real” and “I’m a massive Rammstein fan but it is so cool to see a completely different kind of artist appreciating this kind of music and putting their own spin on it.” In these comments, both artists’ and fans’ ability to appreciate genre flexibility and innovation is presented as a forward-thinking position, in contrast to fuddy-duddy genre purists.

One of the things that’s most interesting about this moment is the coexistence of aughts nostalgia’s reiteration of “The Strokes changed everything” narratives with changed attitudes about gender/race and genre boundaries. Aughts indie artists who are trying to capitalize on this wave of nostalgia will have to re-think their schtick. For example, 2ManyDJs rose to fame and renown in the early aughts for their mash-ups that radically transgressed genre boundaries, like the Nirvana-meets-Destiny’s Child “Smells Like Booty.” Just like Freelance Hellraiser’s “Stroke of Genius,” that mashup showed that the iconic rock song by white guys with guitars was basically identical in form and structure to one by women of color pop stars. I thought that approach was so innovative and interesting that I wrote about it in my dissertation (and first book), but in their late 2022 Essential Mix on BBC Radio 1, that same tactic just felt…mundane. The genre transgression that was fresh and bold in 2002 is just music industry status quo twenty years later. So, as artists recognize changed conditions, I think fans also need to think about which artists they center in their nostalgia: just as the aughts post-punk nostalgia brought needed attention to women of color in the punk and post-punk scenes (ESG, Poly Styrene, etc.), hopefully aughts indie nostalgia can move beyond the politics of representation and think more structurally about the conditions of production both in the early aughts and in the 1970s and how they are so different than the ones in which we find ourselves now.