Our Critical Debate Could Be Your Life

This was originally published on Decemer 2, 2023 on my Substack newsletter. I’m republishing it here to get this post on my platform. (Never trust platforms you don’t own.) If you would like to support the work I do (I don’t get research funds now that I’m not faculty), I’m running a sale on newsletter subscriptions: a year for $24. Offer is good until 23 February 2024.

As Rob Mitchum wrote in Pitchfork’s “Top Singles of 2004” feature, “Appreciating Britney Spears was the final frontier of shedding my old pop-fearing husk, so laced was her music and persona with the red flags of hitting/slaving misogyny, leering pedophilia, and mannequin sexuality.” At the time, Pitchfork was the barometer of serious musical taste, and Spears was, as Mitchum described, widely vilified as the quintessence of corporate pop vacuity. The fact that this once bastion of rockist snobbery had ranked Spears’s “Toxic” as the third best song of 2004 signaled that the critical vibes had shifted: poptimism, or the view that commercial pop traditionally by and for people who weren’t white men had just as much aesthetic heft and value as “serious” genres like rock and (to some extent) hip hop, was firmly institutionalized as the consensus view among music’s elite.

This vibe shift was accelerated by Kelefa Sanneh’s October 31, 2004 New York Times piece “The Rap Against Rockism,” which argued that “Like the anti-disco backlash of 25 years ago, the current rockist consensus seems to reflect not just an idea of how music should be made but also an idea about who should be making it.” Sanneh highlighted the fact that judgments about music were often also judgments about people, such that the disdain for genres like disco or pop was often explicitly couched in homophobic, racist, and sexist terms. Though Ashlee Simpson’s botched lip-synching on Saturday Night Live was the focal point of Sanneh’s analysis, Pitchfork’s choice to hang their poptimist flag on Spears’ single points to her status at the time as the Queen of Pop. Back then, the gatekeepers of musical taste could loudly proclaim their admiration for Spears without seeming conformist or uncritical because the emergence of poptimism made it possible to associate taking pop music seriously with progressive values like feminism and anti-racism. In the early aughts, poptimism was edgy, a break with the rockist, patriarchal, white supremacist status quo.

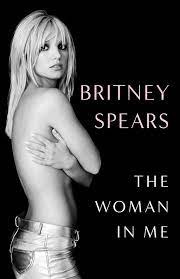

While Spears and her music were central figures in the loud debates music critics and fans had about rockism and poptimism, Spears’s memoir The Woman In Me narrates what it was like to experience that debate and all its tensions as one’s everyday reality. Taken in the context of this contemporaneous debate, Spears’s memoir reads like the rockism-vs-poptimism debate as phenomenology rather than aesthetics. As the living embodiment of pop music, people treated Spears the person and the star with the same disdain they had for her music, and that disdain was compounded by the fact that rockist attitudes towards pop intersect with patriarchal attitudes toward women. At the peak of Spears’s career in the early-to-mid aughts, feminist musicologists and poptimist critics had begun to explicitly connect those two dots. For example, musicologist Susanne Cook’s 2001 Women & Music article “R-E-S-P-E-C-T find out what it means to me: feminist musicology and the abject popular” argues that both popular music and popular music scholarship occupies a “second-class feminized status” in both the academy and society at large. Cook explains, “When popular music colleagues dismiss groups and individuals like N-Sync, Britney Spears, or even Madonna…I sense a real fear of dealing with female desire and female consumption, of valuing women, and especially girls, as thinking, knowledgeable consumers and critics who have enormous power in the commercial and aesthetic marketplaces.” The problem people had with pop music is the same problem they had with Britney herself: they both exhibited the stereotypical and devalued qualities patriarchy traditionally attributes to white women. Echoing Cook’s point that dismissals of Spears reflect a “fear of dealing with female desire,” Spears poses the rhetorical question, “Why did everyone treat me, even when I was a teenager, like I was dangerous?” As NPR music critic Ann Powers tweeted earlier this year, “poptimism once felt feminist” because negative attitudes about pop music’s value were directly tied to patriarchal attitudes about women and our value. The Woman In Me reveals that as both blonde and traditionally beautiful and the world’s biggest pop star, Britney’s daily reality was structured by the systematic devaluation and demonization of both pop music and women. Its insights into her inner thoughts and feelings likewise reveal she had some of the same assessments of these experiences that optimist critics did, namely, that they were shaped not by the quality of her work as an artist, but by patriarchal attitudes toward women.

One of the most interesting things in the book are its discussions of Spears’s artistic decisions. Though I am the kind of nerd who wished the book got into even more detail in its discussion of musical specifics, overall it shows that in the years leading up to her conservatorship, Spears was actively and increasingly in creative control of her recording and performance activities. She refers to Blackout as her creative peak: “Recording for Blackout, I felt so much freedom. Working with amazing producers, I got to play.” Describing this freedom as a “fuck you” to her parents and their attempts to control her career, Spears observes that “the more I started going and doing things myself, the more interesting people started noticing and wanting to work with me.” Far from a dumb blonde controlled by others, Spears was a thoughtful artist and skilled practitioner exercising creative control of her oeuvre–a point many feminist pop music scholars like myself were making at the time. For example, the book details how it was Spears’s idea to collaborate with Madonna on “Me Against The Music,” and what was for me the most fascinating part of the book was her explanation of how she prepared to record “…Baby One More Time” by singing along to Soft Cell’s “Tainted Love.” I had never heard of that fact until I read Spears’s memoir, but it immediately made sense once I read it: the timbre of Spears’s vocals on “…Baby One More Time” strongly echoes Soft Cell frontman Marc Almond’s, the voice sitting low at the back of the mouth. Spears’s “ays” on the opening “Oh baby, baby”s even sound like an attempt at some sort of a British accent. Now’s not the place to dig into the queer readings of Spears’ debut hit that this fact prompts, but it is evidence of both her artistry and her range of influences. And she knew she was a skilled, savvy performer: “For me, performing wasn’t about posing and smiling. Onstage,” she says, “I was like a basketball player driving down the court. I had ball sense, street sense. I was fearless. I knew when to take my shots.” With this insight into Spears’ self-understanding, it makes sense that she was once the biggest pop star in the world: she was talented, shrewd, creative, open to unusual influences, all the things an artistic genius ought to be.

Despite Spears’ internal self-understanding, the external world understood her in vastly different terms. The media–and many music listeners–judged both her and her music for embodying a particular kind of stereotypical white cishetero femininity. For example, after the 2000 Video Music Awards, MTV filmed a segment where Spears had to react to person-on-the-street takes on her performance: “Some of them said I did a good job, but an awful lot of them seemed to be focused on my having worn a skimpy outfit.” More interested in how the performance situated Spears on the virgin/whore dichotomy than they were in the actual music and dancing, viewers evaluated Spears’s work as a performance of (white) femininity. Later in the book, she describes the experience of having her musical performance judged as a performance of femininity in uncannily striking terms:

they point to me and say, ‘Look! A virgin! It’s nobody’s business at all. And it took the focus off me as a musician and a performer. I worked so hard on my music and on my stage shows. But all some reporters could think of to ask me was whether or not my breasts were real (they were, actually) and whether or not my hymen was intact.

Regardless of whether Spears is familiar with Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, in this passage her experience of sexism is analogous to his account of the phenomenology of anti-Black racism. In the fourth chapter of that book, Fanon famously describes the experience of a white child pointing to him and shouting “Look! A negro!”, and how this then both reduces him to an object and makes him feel as though his identity is overdetermined by the qualities of his skin. Fanon argues that this sort of racism prevents him from experiencing the world as a full person, Spears says that this sort of sexism prevented her from experiencing the world as a musician and performer, as people relate to her primarily as a collection of gendered body parts policed for their supposed purity.

When people did bother to talk about Spears’s music itself, they likewise critiqued and policed it for its perceived femininity. As Germanist Andreas Huyssen wrote in 1987, Western modernism “consistently and obsessively genders mass culture and the masses as feminine.” For example, in his essay “On The Fetish Character of Music and the Regression of Listening,” philosopher Theodor Adorno describes popular/commodity music as “as nonsensical as if it had originated in a girls’ school.” Spears’s music is likewise devalued through feminization. And from what she says in the memoir, Spears is–at least these days–well aware that is what was happening. For example, just after her discussion of the 2000 VMAs, she explains that

It felt like every time I turned on an entertainment show, yet another person was taking shots at me, saying I wasn’t ‘authentic.’ I was never quite sure what all these critics thought I was supposed to be doing–a Bob Dylan impression? I was a teenage girl from the South. I signed my name with a heart. I liked looking cute.

Spears’s hyperfeminine gender performance was authentically her: a teenager who imagined herself in the terms of stereotypical white Southern femininity. So these charges of inauthenticity weren’t comparing her music to her personal and/or cultural identity, but to an external standard for “real” music, like Bob Dylan. Dylan wrote his own songs about supposedly deep and often political subjects, was not an especially artful performer, and couldn’t sing and dance as virtuosically as Spears. But he was a man and his music was (supposedly) serious and substantive–enough to eventually win the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature. In other words, Dylan’s music is perceived to be authentic because it performs stereotypical rock masculinity, regardless of how ultimately “constructed” that gender performance is. (There is a long and deep scholarly record demonstrating that 20th century Western notions of musical “authenticity” are themselves performances of an appropriated stereotype of Black masculinity.) Spears’s music was not masculine, and that’s what made it supposedly inauthentic.

The first part of the book gives voice to the tension Spears felt between her artistic skill and accomplishment, on the one hand, and her demonization and dismissal of both her and her music as unacceptably feminine. While scholars like Cook and I used her case to theorize the feminization of popular music, Spears lived it, day in and day out. Understood as a first-person account of the experience of being demonized not for what you do, but for who you are, The Woman In Me’s echoes of Fanon make a lot more sense. The rockist-vs-poptimist debate was at least in part a philosophical debate about abstractions like “high art” and “low art,” and although many poptimist critics like Cook and myself also knew that the stakes of debate impacted our own lived experiences as women making, listening to, and discussing music, Spears’s memoir presents these stakes in their most hyperconcentrated and amplified form. I was deeply invested in poptimism because it addressed my experiences of misogyny in a part of my life that was very important to me. For Spears, the scale of the problem was completely different: this issue shaped the entirety of her lived experience, in no small part because her parents treated her as the very superficial, hypersexual, and hysteric being the media claimed she was.

The second half of the book addresses Spears’s life while she was under the conservatorship of her father and his business partner Robin Greenhill. The tension that structures the first part goes away in this second half, as Spears’ conservators turned her into the empty plastic shell of a performer that she was formerly vilified for purportedly being. Spears was clearly not born a brainless puppet of men in the music industry, but for that reason, it seems, she had to be made into one. As she put it, “the conservatorship stripped me of my womanhood, made me into a child. I became more of an entity than a person onstage. I had always felt music in my bones and my blood; they stole that from me…They wanted to take away that specialness and keep everything as rote as possible. It was death to my creativity as an artist.” Denied any creative input in her work, Spears started to phone it in. And who could blame her for working to rule on gigs that alienated her from her authentic creativity?

The conservatorship started in 2008, and Spears’s clarification that she was quite literally doing the bare minimum at work because that was the only modicum of freedom she had in a situation that was otherwise entirely oppressive and dehumanizing sheds new light on debates in the early 2010s about the extent of her talent as a vocalist. In 2014, a recording of raw (non-Autotuned) vocals for her 2013 single “Alien” was posted to YouTube, and it was far from pitch-perfect. This led outlets like The Daily Beast to publish stories questioning whether Spears could “really” sing. Knowing that Spears was intentionally phoning it in because that’s the most she could do to protest her complete lack of autonomy suggests a new way of interpreting evidence of a possibly less-than-stellar vocal performance from this period: the only way she could exercise any self-determination in her life was to meet expectations as minimally as possible. Always on the cutting edge of pop culture, Spears was “quiet quitting” a decade before that trend went viral.

By the late 2010s, the media was less interested in questioning Spears’s vocal talent and more interested in confirming it. For example, in 2017 the New Zealand Herald reports that “Britney’s original demo for her 2004 smash Toxic has been leaked, and it’s genuinely impressive.” Trashing Spears’s musicianship was no longer a good way to drive clicks and engagement because public attitudes toward her had shifted. In a 2021 interview with Chris Crocker, creator of the infamous “Leave Britney Alone!” meme from 2007, NPR writes, ““Leave Britney alone,” [was] a rallying cry that led to ridicule at the time but has now, 14 years later, become the general consensus.” This growing acceptance of Spears as a musician and a human person reflects broader trends in popular culture and the politics of identity. Just as feminism had gone from an “f-word” nobody would touch to a brand leveraged by everyone from pop stars to influencers to C-suite businesspeople, in the 2010s poptimism ceased to be an avant-garde stance and became industry orthodoxy. As the widespread criticism of former Rolling Stone head Jan Wenner’s 2023 New York Times interview reveals, overtly sexist and racist views about who could and couldn’t be “real” musicians such as Wenner’s have become unacceptable, at least to the mainstream music press.

During the course of Spears’s conservatorship, the world changed from one where demonizing women and pop music together categorically helped police patriarchal racial capitalist distributions of personhood and aesthetic value to one where poptimism and feminism could also be used for those same ends. In this respect, The Woman In Me is a document of a very specific era: the period from the millennium through around 2010, during the last throes of mass rockism and the dawn of poptimism. It is also the last decade before the rise of “post-racial” white supremacy and corporate popular feminism…and the TEA Party. Status differentials regarding music and identity function differently today, as neoliberal ideology, algorithmic technologies, and neofascisms allow for the policing of personhood and aesthetic value in new ways.

For example, the policing of pop stars’ virginity is, in 2023, downright old fashioned. Writing for Jezebel in 2018, Hazel Cills tracked “The Rise and Fall of the Pop Star Purity Ring.” Cills notes that George W. Bush’s 2001 Community-Based Abstinence Education program reshaped sex ed in the U.S. entirely around an abstinence-only ethos, and catalyzed a boom in “purity culture,” which held that the only appropriate sexual choice for unmarried people is abstinence. However, as Cills points out, by the dawn of the Obama era, both the federal funding and the purity vibes vanished, as “Disney’s next class of teen artists like Zendaya, Bella Thorne, and Rowan Blanchard are not only quiet on issues of religion, they have progressive, liberal views on sex: Zendaya advocates for casual sex as long as you get “tested periodically,” Thorne identifies as bisexual, and Blanchard is frequently outspoken about feminism.” The pendulum has swung from “Look! A virgin!” to “When Did Feminism Become a Job Requirement for Female Pop Stars?” and TNI’s own “Is Taylor Swift a Feminist?” Though Spears’s memoir provides phenomenological depth to aughts feminist analyses of the mutual demonization of women and pop music, it speaks to the current state of gender politics and pop music aesthetics only as a point of contrast and a past from which we’ve moved on.

The situation Spears describes in her memoir is neither any better nor any worse than it is today. Patriarchal racial capitalist status differentials still exist and are applied to both people and to music. They just work in different ways now. If Spears is the iconic example of white cishetero women’s experiences of the race and gender politics of popular music at the turn of the millennium, Swift is a good candidate for her successor. The Woman In Me documents the experience of a white patriarchal regime that excludes feminized people and feminized music from being taken seriously as people and as art/artists. Swift, however, is evidence of a newer modality of white patriarchy, one that is more flexible about gender and genre difference so long as the music or musician in question is perceived as oriented to the capacity for private wealth accumulation. Though Swift herself is widely lauded for sticking it to the record companies and re-recording her albums so that she owns the copryights to her songs, she is more like those huge multinational corporations than she is like the vast majority of working musicians (who are more likely to not meet the 1000 streams per month threshold Spotify now requires to pay out royalties on a track). Similarly, while drag performance and ballroom have become routine features of mainstream pop culture, the right has been attempting to criminalize drag in particular in order to target trans and queer people, whom they believe are threats to the private family. RuPaul makes millions on her show while a trans boy in Texas was recently prevented from performing in his school play. Spears was demonized for her identity as a white cishetero woman, but today identity alone isn’t fully determinant of status.

Just as identity itself is no longer a clear index of status, genre is also less singularly determinant of musical status as it was earlier in the millennium. In his fieldwork studying the engineers who built and maintained the recommendation algorithms behind several popular music streaming platforms, anthropologist Nick Seaver found that these engineers are deeply invested in systems that categorize users by their orientation to listening rather than the demographic and identity based systems of traditional radio formats and musical genres. He explains, “people who work on these systems are generally reluctant to recognize demographic categories as technically salient,” categorizing users instead “primarily in terms of musical enthusiasm, or avidity. Avidity manifests as an interest in musical exploration or a willingness to expend effort in pursuit of new music” (3). Seaver’s findings clarify that these engineers implicitly connect demographic identity to musical genre as kindred concepts, and view both as old-fashioned ways of relating to music. In this new algorithmically-curated world, high status is connected to “avidity,” or the eagerness to explore new and different types of music.

Avidity is the explicit rejection of narrow adherence to determinate categories. John Stein, the project lead on Spotify’s flagship genre-less playlist POLLEN similarly describes today’s ideal listener as having surpassed genre’s limits and baggage:

According to Stein, genre is a thing of the past, something people who care about rigid adherence to defined categories use to translate their identities into musical tastes. Also note how the specific genres Stein cites–pop-punk and hip-hop—plot out a white/black racial binary and highlight genre’s very traditional association with race. As Stein implicitly presents it, genres are burdened with the baggage of a racist music industry, baggage that today’s music fans have purportedly left behind in their avid consumption unrestrained by narrow genre boundaries.

The problem with this is that avidity doesn’t actually transcend identity and the systems of oppression that created these identities. As Seaver explains, “when they displace demography with avidity, developers are not only claiming elite cultural status for themselves – figuring themselves as ‘cool’ cultural intermediaries, unlike the prototypical user,” who are commonly figured as “teenage girls who wanted to hear the same pop music on repeat.” In this framework Seaver identified among music recommendation algorithm programmers, low status listenership is defined by its narrow focus on a defined and unchanging range of music. Even though they define status in terms of behavior rather than identity, Seaver’s research subjects still associate low-status listening with teen girls. The “rock” in “rockism” may be just as out of fashion with elites as overt sexism is, but the underlying patriarchal bias remains. (Oops, they did it again, I guess?)

Today, word on the street is that record companies can’t break huge pop stars anymore; although aughts stars like Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, and Niki Minaj still command enormous fan armies, newer artists like Ice Spice have a harder time generating massive, generation-spanning household names for themselves. This, in addition to everything I just discussed, has me less worried that there will be another star like Spears who is the focus of everything patriarchal racial capitalist pop culture loves to hate. Instead, I’m more worried about attempts to literally criminalize certain kinds of musical performances, such as attempts to ban drag performance and to use rap lyrics as evidence of wrongdoing in court. Instead of burning disco records as a proxy for racist and homophobic violence like boomers did in the 1970s, Americans are making it illegal for Black and/or queer people to write and perform music in the first place. On the flip side, with Spotify de-monetizing songs that have less than 1000 streams per month and the bottom falling out of the touring economy, the music industry is increasingly a place where you can make any sort of music you want so long as you are independently wealthy. As we head into the second quarter of the century, it’s increasingly less likely that a lower-middle class girl from rural Louisanna — especially if she’s queer, disabled, and/or not white— could even have a sustainable career in the music business at all. And while I’m certainly glad that public opinion has shifted to Spears’s favor, I also know the struggle against the underlying problems of status and personhood are far from over.